At the start of your PhD journey, you will likely need a research proposal or PhD essay for your application or before commencing with your chapters. In this example, the author reviews the literature on key stages of development from birth to 19 years. The PhD essay covers the main dimensions of human development and provides a detailed description of how children develop throughout the period mentioned above. In the end, the author identifies the key problems associated with child development and provides a set of recommendations to education practitioners.

1. Introduction

The sphere of education is growing at unprecedented rates in both the UK and the world in general according to Statista (2023). As demonstrated by the increasing public interest in preschool learning, many parents are interested in preparing their children for future learning challenges early on and ensuring that high-quality teaching support is provided throughout their childhood and adolescence. With this factor contributing to the global growth of the educational services sector, practitioners operating in it need to better understand how traditional instruments can be adjusted and/or updated for younger audiences (Saracho, 2019). The concept of development stages is usually defined as a sequence of expected development patterns recognised in children between 0 and 19 years old. This advancement includes multiple elements such as knowledge, skills, physiological characteristics, communication, and emotional competencies. The complexity of this process makes it difficult for many educators to properly understand it, which creates barriers on their path to the refinement of their teaching instruments for younger audiences (Kent and Moran, 2019). This assignment aims to analyse key stages of development from birth to 19 years and provide practical guidance and recommendations to practitioners willing to rely on these elements in their development of learning programmes.

2. Development Dimensions

As noted by Barker and Ward (2021), human development is primarily measured across four main dimensions, namely intellectual development; language and communication; personal, emotional, and social development; and physical development. Progression through them is associated with the formation of independence as the intended end outcome. This implies that proper education and training must help young persons become self-sufficient in all four areas by the time they reach the age of 19 years old that is considered the age of maturity in many countries (Watts, 2019). It should also be noted that these four dimensions are not developing at a consistent rate, which means that toddlers/children primarily demonstrate physical advancement and the development of fine and gross motor skills rather than cognitive and communication skills. In addition to these standard discrepancies, learners can demonstrate personal differences adding to the complexity.

3. Key Development Stages

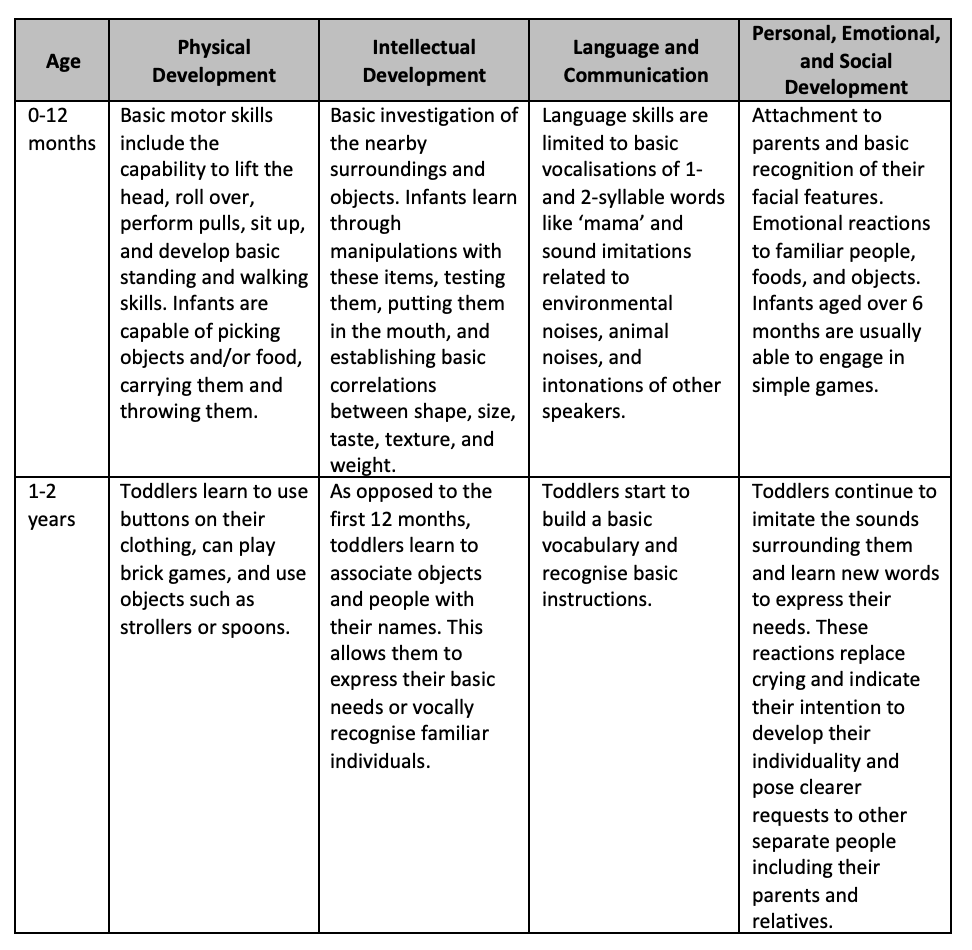

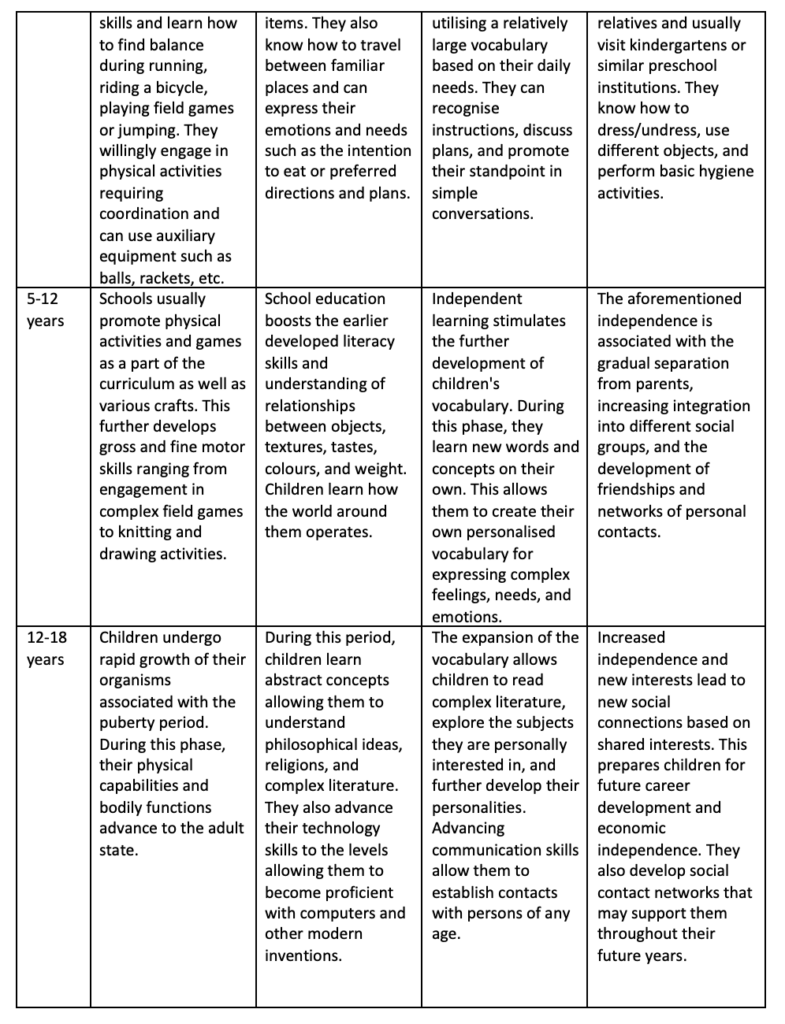

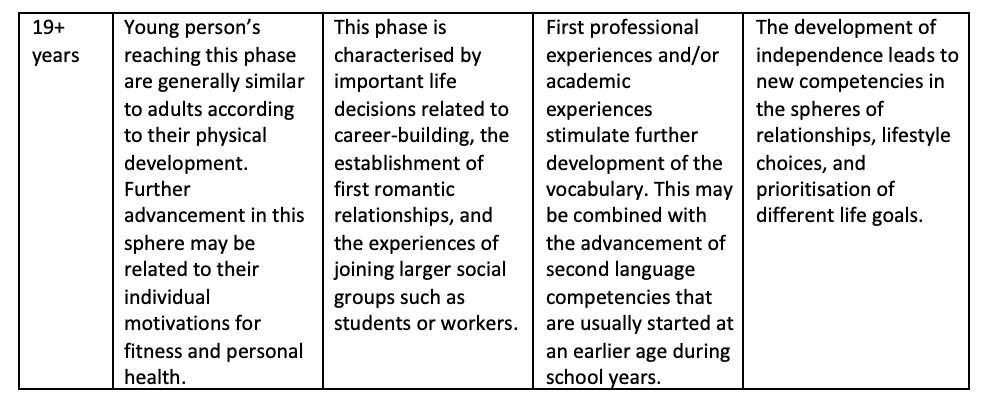

The following child development stages 0-19 years chart UK presents a summary of the four dimensions identified earlier explored within six constituent periods from the birth of an infant to their coming of age (Kucirkova et al., 2019). It can be used as a reference by all UK practitioners willing to incorporate this knowledge in the design of their educational programmes.

Table 1: Key Development Stages

Based on: Charles and Bellinson (2019, p.25); Erstad et al. (2020, p.78); Gullo and Graue (2020, p.201); Henderson et al. (2022, p.90); Wood (2020, p.113)

4. Main Problems Associated with Development Stages

According to Little and Maughan (2020), the development of children throughout the aforementioned stages may be hindered or facilitated by a number of auxiliary factors. First, physical development largely depends on the quality of nutrition, exercise, and the availability of quality health check-ups and medical services. The absence of these elements can lead to weak muscles, obesity, and other problems associated with reduced strength and flexibility. Second, family relationships and social inclusion may affect the personal, emotional, and social development dimensions (Saracho, 2020). The lack of support and guidance can prevent children and young persons from learning more about the world and interiorising some crucial behaviours allowing them to successfully communicate with other people and develop networking capabilities and other soft skills. Third, language development may be affected by background factors such as the encouragement of conversations and the availability of quality communicants (Gheaus et al., 2019). A negative environment spreading the use of swear words or limiting a child’s initiative to talk to family members and other people may hinder the development of capabilities in this sphere.

In this aspect, educational interventions can be beneficial during any of the earlier analysed phases to overcome existing barriers and deficiencies or help young learners develop their strengths through custom-tailored challenges and exercises (Finn-Stevenson, 2018). On the one hand, early development stages are primarily characterised by physical and intellectual development based on the physiological growth of human bodies. From a practitioner, standpoint, this may imply the need to use active games and objects with multiple kinaesthetic/visual/audial features to facilitate learning and help young children overcome their short attention span. With that being said, educators may be limited by physiological barriers, which further increases the significance of using the most effective and optimal tools to fully utilise the available brief ‘windows of opportunity’ (Entwisle, 2018). On the other hand, the school years can be characterised by greater cognitive capabilities and a continued search for new information and interests. Educational interventions combining the provision of such materials with practical exercises within the scope of problem-based learning may be deemed more effective than traditional rote memorisation and other outdated techniques.

5. Recommendations

According to the recommendations presented in contemporary literature, child development stages can be effectively utilised to facilitate educational processes and achieve the best possible results during each phase (Wagner, 2017). First, school and preschool teachers can benefit from collaborating with parents. As found above, children aged 0-12 are dependent on their family members and learn a lot of information from their daily interactions. As a result, the introduction of advanced learning materials and practices can benefit both teachers and parents while close cooperation can help identify any potential problems and help young learners overcome them. Second, the increasing independence associated with intellectual development, language and communication skills development, and personal/emotional/social development should be utilised by offering a larger number of individual assignments (Catalano, 2018). This concept offers a lot of opportunities for integrating blended learning instruments that are presently updated with powerful technologies such as AI. They allow educational platforms to offer customised exercises specifically tailored to student learning needs.

Third, the significance of visual, audial, and kinaesthetic cues during the early school years implies that educational institutions may need to incorporate more advanced instruments to maximise the information transfer effectiveness in classrooms (Connolly et al., 2018). On the one hand, feedback collection and big data analyses can help them identify the most effective educational instruments and regularly update their programmes with better technologies, materials or delivery channels. For example, mobile applications with regular reminders allow educators to subdivide new knowledge into smaller manageable chunks. Their delivery occurs via microlearning schemes, which have proven successful in the case of busy professionals and may be highly valuable for teaching younger children with shorter attention spans (Dohn, 2018). On the other hand, the identified trends imply that teaching techniques need to change with age, which is frequently ignored in contemporary school education according to Rury and Tamura (2019). Such adjustments may be based on data analysis and the aforementioned blended learning instruments showing the tutors what gaps are shared by student groups and must be eliminated as soon as possible.

6. Conclusion

It can be summarised that the six identified development phases vary substantially in terms of the four dimensions mentioned by Barker and Ward (2021). More specifically, infants and toddlers are more focused on acquiring information and building up basic motor skills, which makes it relatively difficult to utilise complex educational techniques (Dohn, 2018). At the same time, greater age is usually associated with developing independence that can be supported via new instruments. Such limitations as the business of modern educational systems and students’ individual characteristics imply that innovative companies offering remote learning, blended learning, and microlearning tools can help practitioners close this gap (Catalano, 2018). These solutions can analyse the patterns demonstrated by individual students and offer personalised support allowing them to specifically address weaker areas. In combination with mobile apps and other innovative information delivery systems, this can close the gap between school-based learning and home learning creating a blended and uniform learning environment uniting all involved stakeholders including parents, students, and teachers (Finn-Stevenson, 2018).

A PhD essay sample like this is only one way a proposal can be completed. Often, choosing your PhD research topic can be the most difficult part before even starting your proposal writing. If you need help refining or selecting your topic, you can get help from our PhD application experts to choose something suitable for your interests and PhD level research.

References

Barker, C. and Ward, E. (2021) Level 1 introduction to health & social care and children & young people’s sectors, London: Hatchette UK.

Catalano, A. (2018) Measurements in distance education: A compendium of instruments, scales, and measures for evaluating online learning, London: Routledge.

Charles, M. and Bellinson, J. (2019) The importance of play in early childhood education: Psychoanalytic, attachment, and developmental perspectives, London: Routledge.

Connolly, M., Eddy-Spicer, D., James, C. and Kruse, S. (2018) The SAGE handbook of school organization, London: SAGE.

Dohn, N. (2018) Designing for learning in a networked world, London: Routledge.

Entwisle, D. (2018) Children, schools, and inequality, London: Routledge.

Erstad, O., Flewitt, R., Kummerling-Meibauer, B. and Pereira, I. (2020) The Routledge handbook of digital literacies in early childhood, London: Routledge.

Finn-Stevenson, M. (2018) Schools of the 21st century: Linking child care and education, London: Routledge.

Gheaus, A., Calder, G. and De Wispelaere, J. (2019) The Routledge handbook of the philosophy of childhood and children, London: Routledge.

Gullo, D. and Graue, M. (2020) Scientific Influences on Early Childhood Education: From Diverse Perspectives to Common Practices, London: Routledge.

Henderson, L., Bussey, K. and Ebrahim, H. (2022) Early Childhood Education and Care in a Global Pandemic: How the Sector Responded, Spoke Back and Generated Knowledge, London: Routledge.

Kent, J. and Moran, M. (2019) Communication for the early years: A holistic approach, London: Routledge.

Kucirkova, N., Rowsell, J. and Falloon, G. (2019) The Routledge international handbook of learning with technology in early childhood, London, UK: Routledge.

Little, M. and Maughan, B. (2020) Child Development, New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Rury, J. and Tamura, E. (2019) The Oxford handbook of the history of education, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saracho, O. (2019) Research in Young Children’s Literacy and Language Development: Language and literacy development for different populations, London: Routledge.

Saracho, O. (2020) Handbook of Research on the Education of Young Children, London: Routledge.

Statista (2023) “Education – Worldwide”, [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/app/education/worldwide [Accessed on 25 March 2023].

Wagner, D. (2017) Learning as development: Rethinking international education in a changing world, London: Routledge.

Watts, M. (2019) The Routledge international handbook of learning, London: Routledge.

Wood, E. (2020) The Routledge reader in early childhood education, London: Routledge.